Difference between revisions of "Columbia Race Riot of 1946"

(Created page with "The ''Columbia Race Riot<ref>Dr. Ikard notes in the preface to his book that some, particularly in the African-American community, have objected to referring to the events of...") |

|||

| (31 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | The ''Columbia Race Riot<ref> | + | [[Category:History]] |

| + | The '''Columbia Race Riot of 1946''' was a violent civil disturbance occurred from February 25-28, 1946 in [[Columbia, Tennessee]].<ref>[https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2021/02/25/columbia-race-riot-wwii-thurgood-marshall/ Lamb, Chris. "America’s first post-World War II race riot led to the near-lynching of Thurgood Marshall." ''The Washington Post.'' 25 Feb. 2021. Web (washingtonpost.com). 3 March 2021.]</ref> | ||

| − | [[ | + | [[File:Nashville banner front page 26 feb 1946.png|thumb|right|Nashville Banner front page, Feb. 26, 1946 (source: newspapers.com).]] |

| + | [[File:Historical marker 3d 83 columbia race riot.jpg|thumb|right|Historical Marker 3D-83 (east side) on East 8th Street in Columbia, describing the Race Riot of February 1946. (8 Feb. 2021).]] | ||

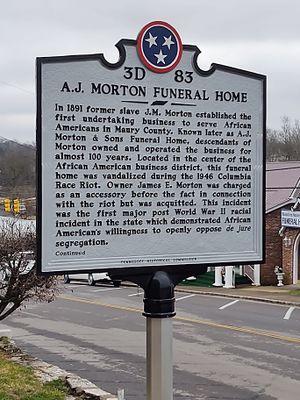

| + | [[File:Historical marker 3d 83 aj morton funeral home.jpg|thumb|right|State Historical Marker on East 8th Street noting the Columbia Race Riot and damage to the Morton funeral home. Note that the other side (east side) of the marker contains different text. (8 Feb. 2021).]] | ||

| − | On February 25, 1946, a disagreement over a radio repair led to a street brawl outside of the Castner-Knott department store in Columbia involving Billy Fleming, a white radio repairman; Gladys Stephenson, a black native of Columbia who was visiting town; and Stephenson's son James, who was a competitive boxer during his service in the United States Navy during World War II.<ref>[https://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entries/columbia-race-riot-1946/ Van West, Carroll. "Columbia Race Riot, 1946." ''Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture.'' Tennessee Historical Society, 1 Mar. 2018. Web. 2 Feb. 2021.]</ref><ref>Ikard, cited ''supra'' at pp. 13-15.</ref><ref>O'Brien, | + | ==Categorization as a "Riot."== |

| + | The use of the term "riot" to describe the events that took place in February 1946 in Columbia has been criticized, in particular on the basis that law enforcement, at least initially, tried to prevent white supremacist violence rather than tacitly or actively promoting it.<ref>Ikard, Robert W. ''No More Social Lynchings.'' Franklin, Hillsboro Press, 1997, p. x. Web (hathitrust.org). 1 Feb. 2021.</ref><ref>Beeler, Dorothy. "Race Riot in Columbia, Tennessee February 25-27, 1946." ''Tennessee Historical Quarterly.'' vol. 39, no. 1 (Spring 1980), p. 49, at p. 53. Web (JSTOR). 8 Feb. 2021.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Prior Incidents of Racial Violence== | ||

| + | [[Lynchings in Maury County | Lynchings]] - the killing of often-innocent people by armed vigilantes, usually as a means to assert white racial supremacy - were an unfortunately common phenomenon in the Southern United States during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, with more than 214 lynchings in Tennessee between 1882 and 1930.<ref>Approximately one person - usually but not always African-American men - was lynched each week on average in the Southern United States between 1882 and 1930. [https://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entries/lynching/ Bennett, Kathy. "Lynching." ''Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture.'' Tennessee Historical Society, 1 Mar. 2018, Web. Accessed 1 Feb. 2021.]</ref> Maury County gained national notoriety for the lynchings of two young African-American men, both accused (with little or no evidence) of having attacked young white women, in 1927 and again in 1933.<ref>Ikard, cited ''supra,'' at pp. 8-9. 118-19.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Across the South, there were numerous incidents of white-on-black violence during and immediately after World War II, perhaps resulting from pent-up frustrations of recently-discharged soldiers and sailors.<ref>Ikard at pp. 115-116.</ref> At the same time, African-American (black) veterans of World War II felt empowered to seek a "double victory" in ending racial segregation at home after defeating fascism abroad.<ref>Ikard at p. 117.</ref> This new attitude of resistance triggered fears of black insurrection (perhaps aligned with Communist revolution) among some whites.<ref>Ikard at pp. 120-122.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Events of February 25-26, 1946== | ||

| + | On February 25, 1946, a disagreement over a radio repair led to a street brawl outside of the Castner-Knott department store in Columbia involving Billy Fleming, a white radio repairman, and World War II veteran; Gladys Stephenson, a black native of Columbia who was visiting town; and Stephenson's son James, who was a competitive boxer during his service in the United States Navy during World War II.<ref>[https://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entries/columbia-race-riot-1946/ Van West, Carroll. "Columbia Race Riot, 1946." ''Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture.'' Tennessee Historical Society, 1 Mar. 2018. Web. 2 Feb. 2021.]</ref><ref>Ikard, cited ''supra'' at pp. 13-15.</ref><ref>O'Brien, Gail Williams. ''The Color of the Law: Race, Violence, and Justice in the Post-World War II South.'' Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1999, pp. 9-11.</ref><ref>[https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHK-Q3RX-LZZW?i=478&cat=451514 "Two Negroes Held For Attack on Veteran." ''The Daily Herald.'' 25 Feb. 1946. p. 1. Web (familysearch.org). 14 March 2021.]</ref> Though the Stephensons were arrested and initially charged with disturbing the peace, their warrants were changed to "attempted murder" after the intervention of Fleming's father.<ref>Ikard at pp. 15-16.</ref>Fearing that the Stephensons would be lynched if they remained in the county jail. local black businessmen led by Julius Blair posted bail (which had been raised from $50 to $3,500) and the Stephensons were released.<ref>O'Brien at pp. 11-12</ref><ref>Ikard at pp. 15-16.</ref> Later that evening, James Stephenson was later escorted out of the county for his own safety.<ref>Ikard at pp. 23-24.</ref><ref>O'Brien at 13-15.</ref> | ||

A mob of white citizens began forming that afternoon in downtown Columbia, and some of the town's black citizens began arriving, armed, to the area then known as the "Mink Slide" (part of a larger area known as "The Bottom" between East 8th and 9th Streets south of the county courthouse) to defend the black-owned businesses there.<ref>O'Brien at pp. 15-17.</ref><ref>Ikard at pp. 20-23.</ref><ref>Van West, cited ''supra.''</ref> | A mob of white citizens began forming that afternoon in downtown Columbia, and some of the town's black citizens began arriving, armed, to the area then known as the "Mink Slide" (part of a larger area known as "The Bottom" between East 8th and 9th Streets south of the county courthouse) to defend the black-owned businesses there.<ref>O'Brien at pp. 15-17.</ref><ref>Ikard at pp. 20-23.</ref><ref>Van West, cited ''supra.''</ref> | ||

| − | Hearing | + | Hearing gunfire coming from the "Mink Slide," Columbia Police Chief Walter Griffin and three officers (nearly half of the town's entire police force at the time) walked down to East 8th Street at about 9 p.m. to investigate and break up the black crowd. Behind the officers was a mob of whites. In the darkness of that night, and with confused shouts from the crowd of "halt!" and "fire!", the entrenched blacks shot and wounded the police officers.<ref>Ikard at pp. 27-28.</ref><ref>O'Brien at pp. 17-18.</ref> |

| − | At | + | At about the same time as the four officers were shot in Columbia, Governor James McCord called Public Safety Commissioner Lynn Bomar (who had command of the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tennessee_Highway_Patrol | Tennessee Highway Patrol]) and ordered him to Columbia.<ref>Ikard at p. 47. Note that Ikard gives the time of this phone call as 8:30 p.m. and that Commissioner Bomar was in Nashville for this phone call.</ref><ref>O'Brien at p. 18. Note that O'Brien states that there was a phone call after the officers were shot, or after 9 p.m. and that Commissioner Bomar was already near Spring Hill.</ref> Commissioner Bomar assessed the situation on his arrival and concluded that the main threat came from the armed blacks in the Bottom and sought to deputize the white civilian mob and arm them with weapons from the Tennessee State Guard armory -- a move that the State Guardsmen strongly, and successfully, objected to.<ref>Ikard at p. 32.</ref><ref>O'Brien at pp. 18-19.</ref> |

Meanwhile, Bomar ordered his Highway Patrolmen to Columbia and the State Guard mobilized; the Highway Patrol and State Guard agreed, due to the time needed for their patrolmen and troops to arrive, to a plan to cordon off the area but not to advance into the Bottom until daybreak; this delay afforded many of the black citizens of the area to leave the neighborhood in the night.<ref>Ikard at p.34</ref><ref>O'Brien at p. 20.</ref>. | Meanwhile, Bomar ordered his Highway Patrolmen to Columbia and the State Guard mobilized; the Highway Patrol and State Guard agreed, due to the time needed for their patrolmen and troops to arrive, to a plan to cordon off the area but not to advance into the Bottom until daybreak; this delay afforded many of the black citizens of the area to leave the neighborhood in the night.<ref>Ikard at p.34</ref><ref>O'Brien at p. 20.</ref>. | ||

| − | During the night, members of the white mob heckled the state authorities for their inaction; two young white men tried to sneak into the Bottom themselves and were fired upon.<ref>Ikard at pp. 33-34.</ref> During the early morning (before the agreed-upon time of daybreak) Bomar and a small group of his patrolmen into James Morton's home without a warrant, arresting about a dozen people, ransacking the place and confiscating guns, as well alcohol and Morton's wife's jewelry.<ref>Ikard at pp. 35-36.</ref><ref>O'Brien at p. 21.</ref> The Highway | + | During the night, members of the white mob heckled the state authorities for their inaction; two young white men (James Beard and Claude Bogie) tried to sneak into the Bottom themselves (allegedly with the intent to set the "Mink Slide" ablaze) and were fired upon by one of the black men holed-up nearby.<ref>Ikard at pp. 33-34.</ref> During the early morning (before the agreed-upon time of daybreak) Bomar and a small group of his patrolmen into James Morton's home without a warrant, arresting about a dozen people, ransacking the place, and confiscating guns, as well alcohol and Morton's wife's jewelry.<ref>Ikard at pp. 35-36.</ref><ref>O'Brien at p. 21.</ref> |

| + | |||

| + | The Highway Patrolmen (with local lawmen, but without coordinating with the State Guard) advanced in force at 6 a.m., wantonly vandalizing local businesses in the Bottom (most notoriously, scrawling "KKK" on caskets in Morton's funeral home) and arresting and beating blacks found in the area.<ref>Ikard at pp. 37-40.</ref><ref>O'Brien at pp. 23-27.</ref> A gunfight occurred at Saul Blair's barbershop, where "Rooster Bill" Pillow and "Papa" Kennedy exchanged shots with some of the patrolmen; but otherwise the Highway Patrol's sweep met no resistance.<ref>Ikard at pp. 38-40.</ref> The State Guardsmen nearby struggled to keep white civilians out of the area to prevent vigilantes from joining in on the fracas.<ref>Ikard at p. 39.</ref> About 31 people were arrested during the early hours of February 26.<ref>Ikard at p. 41.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Later on February 26, Bomar obtained warrants and Sheriff Underwood deputized the Highway Patrolmen and Guardsmen to do a city-wide search of black homes for guns and ammunition. Over the next several days, dozens of black men and women were rounded up, often on flimsy pretexts.<ref>Ikard at p. 42.</ref> Governor McCord visited Columbia and decided against declaring martial law, though the State Guard remained in Columbia until the evening of March 3.<ref>[https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHK-Q3RX-LZZW?i=478&cat=451514 Ketterson, Tom (UPI). "70 Are Held In Local Jail After Seven Are Wounded In Night-Long Racial Riots; Weapons To Be Seized By Newly-Deputized Officers." ''The Daily Herald.'' 26 Feb. 1946. p. 1. Web (familysearch.org). 14 March 2021.]</ref><ref>[https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHK-Q3RX-LZN5?i=520&cat=451514 "City Nears Normal As Restrictions End; Guard Goes Out Damages Repaired; Few In Jail When Habeas Granted." ''The Daily Herald.'' 4 March 1946. p. 1. Web (familysearch.org). 15 March 2021.]</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Aftermath: Jailings, Litigation, and Investigations== | ||

| + | By February 28, over 100 black citizens had been arrested and held without bail or legal representation for days.<ref>Ikard at 45-47.</ref>Two black men, James "Digger" Johnson, and Willie Gordon, were shot and killed by lawmen after being interrogated; the two allegedly grabbed some of the guns confiscated during the February 26 raid that had been stacked nearby in the jail in an attempt to escape.<ref>Ikard at 47-48.</ref><ref>O'Brien at 31-32.</ref><ref>King, Gilbert. ''Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New America.'' New York, Harper Perennial, 2012. p. 13.</ref> Some of the prisoners were transferred to Nashville to relieve overcrowding after the deaths of Johnson and Gordon; all of the prisoners were eventually released on bail or without charges by the second week of March.<ref>Ikard at p. 50. Note that Tommy Baxter died of illness after being jailed.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Columbia Riot became a cause for liberal, leftist, and black civil rights organizations nationwide; and black newspapers sent reporters to follow the cases.<ref>Ikard at pp. 54-58.</ref><ref>For an example of propaganda related to the Columbia Race Riots from the political left, see [https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/002929092 Minor, Robert. ''Lynching and Frame-Up in Tennessee.'' New York, New Century Publishers, 1946. Web (hathitrust.org). 8 Feb. 2021.] This pamphlet, written by a member of the Communist Party, is highly critical of law enforcement in Tennessee as well as capitalist business interests; despite this, Dr. Ikard describes it as "as accurate as any other by 'outsiders.'" (Ikard at p. 56).</ref> Lawyers for the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/NAACP National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)] - Thurgood Marshall (later the first African-American Supreme Court Justice), Z. Alexander Looby (an immigrant from Antigua and lawyer in Nashville), and Maurice Weaver (a white lawyer from Chattanooga) - arrived following the mass arrests on February 26.<ref>Ikard at pp. 51-52.</ref><ref>King at pp. 8-10.</ref><ref>[https://www.tba.org/?pg=TennesseeBarJournal Hudson, David. "Thurgood Marshall in Tennessee: His Defense of Accused Rioters, His Near-Miss With a Lynch Mob." ''Tennessee Bar Journal.'' vol. 56. no. 8 (Sept-Oct. 2020), pp. 16-21. Web (tba.org). 8 Feb. 2021.]</ref> Though the black defendants were initially skeptical of the NAACP outsiders, the persistence and enthusiasm of Weaver and Looby persuaded many of them to seek their assistance.<ref>Ikard at p. 53.</ref> Other NAACP lawyers later joined the defense team. <ref>Ikard at p. 60.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Federal Government also became involved in the aftermath of the Columbia Race Riot, after U.S. Attorney Horace Frierson requested the FBI to investigate in March.<ref>Ikard at pp. 50, 59.</ref> A Nashville-based federal grand jury issued a report during the summer of 1946 concluding that there was no evidence of any violation of federal laws.<ref>Ikard at p. 76.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Cases were brought before the Maury County grand jury by District Attorney Paul Bumpus on March 22.<ref>Ikard at p. 60.</ref> After challenging Maury County's practices which effectively excluded blacks from serving on juries, the NAACP legal team sought a change in venue for the most substantial of the cases (accusing the Saul and Julius Blair, James Morton, and others of inciting the shooting of the four Columbia police officers on the evening of February 25; as well as a second count charging all 25 with attempted murder); instead of the hoped-for change to Davidson County, however, Judge Joe Ingram transferred the cases to Lawrence County instead.<ref>Ikard at pp. 60-62.</ref> After six weeks of jury selection, a jury of twelve white men was selected, and the trial in ''State of Tennessee v. Sol (Saul) Blair'' started.<ref>Ikard at pp. 84-85.</ref> The prosecution team (led by District Attorney Bumpus) called numerous witnesses; many of whom were artfully cross-examined by Weaver, Looby and Howard Law professor Leon Ransom (Marshall was unable to participate in this trial due to illness).<ref>Ikard at pp. 84-101 presents a detailed account of the witness testimony and arguments of counsel.</ref><ref>Hudson at p. 20.</ref>In closing arguments, Ransom argued that the black defendants were reasonably afraid of a white mob. Weaver argued that his defendants were standing for democratic values against authoritarianism. Looby's argument was lawyerly, arguing that there was no evidence of a conspiracy by his defendants to murder anyone and that his defendants were scapegoats for racism and governmental incompetence. District Attorney Bumpus's closing argument cast the white community as victims and assailed outsider agitators and "anarchists."<ref>Ikard at pp. 97-101.</ref> The two-week trial ended on October 4, and after two hours of deliberation 23 of the 25 black defendants were acquitted (the jury found Robert Gentry and John McGivens and guilty of attempted murder).<ref>Beeler, cited ''supra'', at p. 59.</ref><ref>Ikard at p. 102.</ref><ref>[https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-13RX-F6B5?i=389&cat=451514 "23 Columbia Negroes Freed, 2 Guilty Ask For New Trial." ''The Daily Herald.'' 5 Oct. 1946. p. 1. Web (familysearch.org). 15 March 2021.]</ref>This result stunned many locals in Lawrence and Maury counties,<ref>Beeler at p. 59.</ref><ref>Ikard at p. 102.</ref><ref>Though the ''Daily Herald'' editorial the day after the verdict cited the outcome as proof that blacks could receive a fair trial in the South, the ''Herald'' clearly implied that some in the community found the outcome upsetting: "Regardless of what anyone may think of the verdict, and every citizen has a right to his own opinion on that, there is one thing that cannot be disputed.... It may be that some guilty went free; it is certain that none who were innocent were found guilty." [https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-B3RX-F6D2?i=390&cat=451514 "No Prejudice Here." (editorial). ''The Daily Herald.'' 5 Oct. 1946. p. 2. Web (familysearch.org). 15 March 2021.]</ref> though it likely resulted from the conflicting and incomplete evidence the prosecution presented as to which defendants had actually been involved in the shooting.<ref>Ikard at pp. 103-104.</ref> The charges against Gentry and McGivens (as well as a pending case against the Stephensons) were later dropped for lack of evidence.<ref>Ikard at p. 104.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | A second trial began in Columbia for Papa Kennedy and Rooster Bill Pillow (both charged with wounding police officers during the gunfight at Saul Blair's barbershop on the morning of February 26) on November 15.<ref>Ikard at p. 108.</ref> Looby, Weaver, and Marshall defended the two in this second trial, which lasted four days; the trial ended with a split verdict, finding Kennedy (who acted surly during his testimony) guilty of attempted murder in the second degree, but acquitting Pillow.<ref>King at pp. 7-20.</ref><ref>Hudson at p. 20.</ref><ref>Ikard at pp. 108-111.</ref> Kennedy ended up being the only person to be punished for the events of February 25-26, serving nine months in state prison.<ref>Ikard at p. 113.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Local law enforcement was bitter at the outcome of the Pillow-Kennedy trial.<ref>Ikard at p. 111.</ref> As Looby, Marshall, Weaver, and a newspaper reporter left town in Looby's automobile on the night of November 18, they were pulled over by three cars driven by local policemen, county sheriff's deputies, and Tennessee Highway Patrolmen. The law enforcement officers searched their car and, finding nothing, let them proceed. Marshall (who had been driving) switched seats with Looby. Moments later, the lawyers were stopped again, and the officers arrested Marshall on the pretext of "drunken driving" even though (by this point) he was a passenger.<ref>Ikard at pp. 110-111.</ref><ref>King at pp.14-16.</ref> Marshall was put in an unmarked car and Looby was told not to follow, an order he disobeyed out of the fear that Marshall might be delivered into the hands of a white lynch mob.<ref>Ikard at p. 112.</ref><ref>King at pp. 17-19.</ref><ref>Hudson at pp. 20-21</ref>. After a circuitous journey through dark streets (with Looby following closely behind), the car carrying Marshall stopped at the county courthouse, and Marshall was presented before Magistrate J. J. Pogue. Pogue found no probable cause for Marshall's arrest (seeing, and smelling, no evidence that he had been drinking) and ordered him released.<ref>Ikard at p. 111.</ref><ref>King at pp. 18-19.</ref><ref>[https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-B3RX-FDYK?i=637&cat=451514 "NAACP Lawyers' Auto Searched, Weaver Protests." ''The Daily Herald.'' 19 Nov. 1946. pp. 1. 3. Web (familysearch.org). 15 March 2021.]</ref> The lawyers left again for Nashville using a different car to avoid further harassment.<ref>Ikard at pp. 111-112.</ref> | |

| − | + | ==Legacy== | |

| + | Some have argued that the Columbia Race Riot of 1946 helped to improve race relations in Maury County, with African-Americans gaining more respect from their white peers.<ref>Ikard at pp. 128-130.</ref><ref>[https://timmwood.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/columbia-race-riot.pdf Wood, Tim. "Fight to End Racial Prejudice - 1946 race riots." January 2014. Web. 8 Feb. 2021.] Wood cites O'Brien, cited ''supra'', at 247-248.</ref> Others have noted that it helped the NAACP and other organizations lobby the administration of President Harry S. Truman to create the President's Committee on Civil Rights, thus helping to lay the groundwork for federal civil rights legislation in the 1950s and 1960s.<ref>Beeler, cited ''supra'' at pp. 60-61.</ref><ref>Van West, cited ''supra.''</ref><ref>[https://www.columbiadailyherald.com/story/news/2021/02/24/aftermath-1946-columbia-dubbed-riot-necessary-change/4553239001/ Price, Tom and McClellan, JoAnn. "Aftermath of 1946: Dubbed 'riot' was necessary for change in Columbia, America." ''The Daily Herald.'' 23 Feb. 2021. Web (columbiadailyherald.com). 27 Feb. 2021.]</ref><ref>The east side of State Historical Marker 3D-83, on East 8th Street in Columbia, contains a similar claim.</ref> | ||

| + | A historical marker marking the site of the events was installed in 2016.<ref>[https://www.columbiadailyherald.com/in-depth/news/2021/02/25/dispute-over-broken-radio-columbia-tenn-set-stage-civil-rights-movement/4498876001/ Christen, Mike. "How a dispute over a broken radio launched a civil rights movement." ''The Daily Herald.'' 24 Feb. 2021. Web (columbiadailyherald.com). 25 Feb. 2021.]</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==References and Footnotes== | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==External Links== | ||

| + | * [https://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entries/columbia-race-riot-1946/ ''Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture'' article.] | ||

| + | * [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Columbia,_Tennessee#Columbia_race_riot_of_1946 ''Wikipedia article on Columbia, containing a section on the race riot.] | ||

| + | * [https://www.remember1946.com/ Remember 1946 (75th Anniversary events)] | ||

Latest revision as of 01:31, 15 March 2021

The Columbia Race Riot of 1946 was a violent civil disturbance occurred from February 25-28, 1946 in Columbia, Tennessee.[1]

Contents

Categorization as a "Riot."

The use of the term "riot" to describe the events that took place in February 1946 in Columbia has been criticized, in particular on the basis that law enforcement, at least initially, tried to prevent white supremacist violence rather than tacitly or actively promoting it.[2][3]

Prior Incidents of Racial Violence

Lynchings - the killing of often-innocent people by armed vigilantes, usually as a means to assert white racial supremacy - were an unfortunately common phenomenon in the Southern United States during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, with more than 214 lynchings in Tennessee between 1882 and 1930.[4] Maury County gained national notoriety for the lynchings of two young African-American men, both accused (with little or no evidence) of having attacked young white women, in 1927 and again in 1933.[5]

Across the South, there were numerous incidents of white-on-black violence during and immediately after World War II, perhaps resulting from pent-up frustrations of recently-discharged soldiers and sailors.[6] At the same time, African-American (black) veterans of World War II felt empowered to seek a "double victory" in ending racial segregation at home after defeating fascism abroad.[7] This new attitude of resistance triggered fears of black insurrection (perhaps aligned with Communist revolution) among some whites.[8]

Events of February 25-26, 1946

On February 25, 1946, a disagreement over a radio repair led to a street brawl outside of the Castner-Knott department store in Columbia involving Billy Fleming, a white radio repairman, and World War II veteran; Gladys Stephenson, a black native of Columbia who was visiting town; and Stephenson's son James, who was a competitive boxer during his service in the United States Navy during World War II.[9][10][11][12] Though the Stephensons were arrested and initially charged with disturbing the peace, their warrants were changed to "attempted murder" after the intervention of Fleming's father.[13]Fearing that the Stephensons would be lynched if they remained in the county jail. local black businessmen led by Julius Blair posted bail (which had been raised from $50 to $3,500) and the Stephensons were released.[14][15] Later that evening, James Stephenson was later escorted out of the county for his own safety.[16][17]

A mob of white citizens began forming that afternoon in downtown Columbia, and some of the town's black citizens began arriving, armed, to the area then known as the "Mink Slide" (part of a larger area known as "The Bottom" between East 8th and 9th Streets south of the county courthouse) to defend the black-owned businesses there.[18][19][20]

Hearing gunfire coming from the "Mink Slide," Columbia Police Chief Walter Griffin and three officers (nearly half of the town's entire police force at the time) walked down to East 8th Street at about 9 p.m. to investigate and break up the black crowd. Behind the officers was a mob of whites. In the darkness of that night, and with confused shouts from the crowd of "halt!" and "fire!", the entrenched blacks shot and wounded the police officers.[21][22]

At about the same time as the four officers were shot in Columbia, Governor James McCord called Public Safety Commissioner Lynn Bomar (who had command of the | Tennessee Highway Patrol) and ordered him to Columbia.[23][24] Commissioner Bomar assessed the situation on his arrival and concluded that the main threat came from the armed blacks in the Bottom and sought to deputize the white civilian mob and arm them with weapons from the Tennessee State Guard armory -- a move that the State Guardsmen strongly, and successfully, objected to.[25][26]

Meanwhile, Bomar ordered his Highway Patrolmen to Columbia and the State Guard mobilized; the Highway Patrol and State Guard agreed, due to the time needed for their patrolmen and troops to arrive, to a plan to cordon off the area but not to advance into the Bottom until daybreak; this delay afforded many of the black citizens of the area to leave the neighborhood in the night.[27][28].

During the night, members of the white mob heckled the state authorities for their inaction; two young white men (James Beard and Claude Bogie) tried to sneak into the Bottom themselves (allegedly with the intent to set the "Mink Slide" ablaze) and were fired upon by one of the black men holed-up nearby.[29] During the early morning (before the agreed-upon time of daybreak) Bomar and a small group of his patrolmen into James Morton's home without a warrant, arresting about a dozen people, ransacking the place, and confiscating guns, as well alcohol and Morton's wife's jewelry.[30][31]

The Highway Patrolmen (with local lawmen, but without coordinating with the State Guard) advanced in force at 6 a.m., wantonly vandalizing local businesses in the Bottom (most notoriously, scrawling "KKK" on caskets in Morton's funeral home) and arresting and beating blacks found in the area.[32][33] A gunfight occurred at Saul Blair's barbershop, where "Rooster Bill" Pillow and "Papa" Kennedy exchanged shots with some of the patrolmen; but otherwise the Highway Patrol's sweep met no resistance.[34] The State Guardsmen nearby struggled to keep white civilians out of the area to prevent vigilantes from joining in on the fracas.[35] About 31 people were arrested during the early hours of February 26.[36]

Later on February 26, Bomar obtained warrants and Sheriff Underwood deputized the Highway Patrolmen and Guardsmen to do a city-wide search of black homes for guns and ammunition. Over the next several days, dozens of black men and women were rounded up, often on flimsy pretexts.[37] Governor McCord visited Columbia and decided against declaring martial law, though the State Guard remained in Columbia until the evening of March 3.[38][39]

Aftermath: Jailings, Litigation, and Investigations

By February 28, over 100 black citizens had been arrested and held without bail or legal representation for days.[40]Two black men, James "Digger" Johnson, and Willie Gordon, were shot and killed by lawmen after being interrogated; the two allegedly grabbed some of the guns confiscated during the February 26 raid that had been stacked nearby in the jail in an attempt to escape.[41][42][43] Some of the prisoners were transferred to Nashville to relieve overcrowding after the deaths of Johnson and Gordon; all of the prisoners were eventually released on bail or without charges by the second week of March.[44]

The Columbia Riot became a cause for liberal, leftist, and black civil rights organizations nationwide; and black newspapers sent reporters to follow the cases.[45][46] Lawyers for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) - Thurgood Marshall (later the first African-American Supreme Court Justice), Z. Alexander Looby (an immigrant from Antigua and lawyer in Nashville), and Maurice Weaver (a white lawyer from Chattanooga) - arrived following the mass arrests on February 26.[47][48][49] Though the black defendants were initially skeptical of the NAACP outsiders, the persistence and enthusiasm of Weaver and Looby persuaded many of them to seek their assistance.[50] Other NAACP lawyers later joined the defense team. [51]

The Federal Government also became involved in the aftermath of the Columbia Race Riot, after U.S. Attorney Horace Frierson requested the FBI to investigate in March.[52] A Nashville-based federal grand jury issued a report during the summer of 1946 concluding that there was no evidence of any violation of federal laws.[53]

Cases were brought before the Maury County grand jury by District Attorney Paul Bumpus on March 22.[54] After challenging Maury County's practices which effectively excluded blacks from serving on juries, the NAACP legal team sought a change in venue for the most substantial of the cases (accusing the Saul and Julius Blair, James Morton, and others of inciting the shooting of the four Columbia police officers on the evening of February 25; as well as a second count charging all 25 with attempted murder); instead of the hoped-for change to Davidson County, however, Judge Joe Ingram transferred the cases to Lawrence County instead.[55] After six weeks of jury selection, a jury of twelve white men was selected, and the trial in State of Tennessee v. Sol (Saul) Blair started.[56] The prosecution team (led by District Attorney Bumpus) called numerous witnesses; many of whom were artfully cross-examined by Weaver, Looby and Howard Law professor Leon Ransom (Marshall was unable to participate in this trial due to illness).[57][58]In closing arguments, Ransom argued that the black defendants were reasonably afraid of a white mob. Weaver argued that his defendants were standing for democratic values against authoritarianism. Looby's argument was lawyerly, arguing that there was no evidence of a conspiracy by his defendants to murder anyone and that his defendants were scapegoats for racism and governmental incompetence. District Attorney Bumpus's closing argument cast the white community as victims and assailed outsider agitators and "anarchists."[59] The two-week trial ended on October 4, and after two hours of deliberation 23 of the 25 black defendants were acquitted (the jury found Robert Gentry and John McGivens and guilty of attempted murder).[60][61][62]This result stunned many locals in Lawrence and Maury counties,[63][64][65] though it likely resulted from the conflicting and incomplete evidence the prosecution presented as to which defendants had actually been involved in the shooting.[66] The charges against Gentry and McGivens (as well as a pending case against the Stephensons) were later dropped for lack of evidence.[67]

A second trial began in Columbia for Papa Kennedy and Rooster Bill Pillow (both charged with wounding police officers during the gunfight at Saul Blair's barbershop on the morning of February 26) on November 15.[68] Looby, Weaver, and Marshall defended the two in this second trial, which lasted four days; the trial ended with a split verdict, finding Kennedy (who acted surly during his testimony) guilty of attempted murder in the second degree, but acquitting Pillow.[69][70][71] Kennedy ended up being the only person to be punished for the events of February 25-26, serving nine months in state prison.[72]

Local law enforcement was bitter at the outcome of the Pillow-Kennedy trial.[73] As Looby, Marshall, Weaver, and a newspaper reporter left town in Looby's automobile on the night of November 18, they were pulled over by three cars driven by local policemen, county sheriff's deputies, and Tennessee Highway Patrolmen. The law enforcement officers searched their car and, finding nothing, let them proceed. Marshall (who had been driving) switched seats with Looby. Moments later, the lawyers were stopped again, and the officers arrested Marshall on the pretext of "drunken driving" even though (by this point) he was a passenger.[74][75] Marshall was put in an unmarked car and Looby was told not to follow, an order he disobeyed out of the fear that Marshall might be delivered into the hands of a white lynch mob.[76][77][78]. After a circuitous journey through dark streets (with Looby following closely behind), the car carrying Marshall stopped at the county courthouse, and Marshall was presented before Magistrate J. J. Pogue. Pogue found no probable cause for Marshall's arrest (seeing, and smelling, no evidence that he had been drinking) and ordered him released.[79][80][81] The lawyers left again for Nashville using a different car to avoid further harassment.[82]

Legacy

Some have argued that the Columbia Race Riot of 1946 helped to improve race relations in Maury County, with African-Americans gaining more respect from their white peers.[83][84] Others have noted that it helped the NAACP and other organizations lobby the administration of President Harry S. Truman to create the President's Committee on Civil Rights, thus helping to lay the groundwork for federal civil rights legislation in the 1950s and 1960s.[85][86][87][88]

A historical marker marking the site of the events was installed in 2016.[89]

References and Footnotes

- ↑ Lamb, Chris. "America’s first post-World War II race riot led to the near-lynching of Thurgood Marshall." The Washington Post. 25 Feb. 2021. Web (washingtonpost.com). 3 March 2021.

- ↑ Ikard, Robert W. No More Social Lynchings. Franklin, Hillsboro Press, 1997, p. x. Web (hathitrust.org). 1 Feb. 2021.

- ↑ Beeler, Dorothy. "Race Riot in Columbia, Tennessee February 25-27, 1946." Tennessee Historical Quarterly. vol. 39, no. 1 (Spring 1980), p. 49, at p. 53. Web (JSTOR). 8 Feb. 2021.

- ↑ Approximately one person - usually but not always African-American men - was lynched each week on average in the Southern United States between 1882 and 1930. Bennett, Kathy. "Lynching." Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Tennessee Historical Society, 1 Mar. 2018, Web. Accessed 1 Feb. 2021.

- ↑ Ikard, cited supra, at pp. 8-9. 118-19.

- ↑ Ikard at pp. 115-116.

- ↑ Ikard at p. 117.

- ↑ Ikard at pp. 120-122.

- ↑ Van West, Carroll. "Columbia Race Riot, 1946." Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Tennessee Historical Society, 1 Mar. 2018. Web. 2 Feb. 2021.

- ↑ Ikard, cited supra at pp. 13-15.

- ↑ O'Brien, Gail Williams. The Color of the Law: Race, Violence, and Justice in the Post-World War II South. Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1999, pp. 9-11.

- ↑ "Two Negroes Held For Attack on Veteran." The Daily Herald. 25 Feb. 1946. p. 1. Web (familysearch.org). 14 March 2021.

- ↑ Ikard at pp. 15-16.

- ↑ O'Brien at pp. 11-12

- ↑ Ikard at pp. 15-16.

- ↑ Ikard at pp. 23-24.

- ↑ O'Brien at 13-15.

- ↑ O'Brien at pp. 15-17.

- ↑ Ikard at pp. 20-23.

- ↑ Van West, cited supra.

- ↑ Ikard at pp. 27-28.

- ↑ O'Brien at pp. 17-18.

- ↑ Ikard at p. 47. Note that Ikard gives the time of this phone call as 8:30 p.m. and that Commissioner Bomar was in Nashville for this phone call.

- ↑ O'Brien at p. 18. Note that O'Brien states that there was a phone call after the officers were shot, or after 9 p.m. and that Commissioner Bomar was already near Spring Hill.

- ↑ Ikard at p. 32.

- ↑ O'Brien at pp. 18-19.

- ↑ Ikard at p.34

- ↑ O'Brien at p. 20.

- ↑ Ikard at pp. 33-34.

- ↑ Ikard at pp. 35-36.

- ↑ O'Brien at p. 21.

- ↑ Ikard at pp. 37-40.

- ↑ O'Brien at pp. 23-27.

- ↑ Ikard at pp. 38-40.

- ↑ Ikard at p. 39.

- ↑ Ikard at p. 41.

- ↑ Ikard at p. 42.

- ↑ Ketterson, Tom (UPI). "70 Are Held In Local Jail After Seven Are Wounded In Night-Long Racial Riots; Weapons To Be Seized By Newly-Deputized Officers." The Daily Herald. 26 Feb. 1946. p. 1. Web (familysearch.org). 14 March 2021.

- ↑ "City Nears Normal As Restrictions End; Guard Goes Out Damages Repaired; Few In Jail When Habeas Granted." The Daily Herald. 4 March 1946. p. 1. Web (familysearch.org). 15 March 2021.

- ↑ Ikard at 45-47.

- ↑ Ikard at 47-48.

- ↑ O'Brien at 31-32.

- ↑ King, Gilbert. Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New America. New York, Harper Perennial, 2012. p. 13.

- ↑ Ikard at p. 50. Note that Tommy Baxter died of illness after being jailed.

- ↑ Ikard at pp. 54-58.

- ↑ For an example of propaganda related to the Columbia Race Riots from the political left, see Minor, Robert. Lynching and Frame-Up in Tennessee. New York, New Century Publishers, 1946. Web (hathitrust.org). 8 Feb. 2021. This pamphlet, written by a member of the Communist Party, is highly critical of law enforcement in Tennessee as well as capitalist business interests; despite this, Dr. Ikard describes it as "as accurate as any other by 'outsiders.'" (Ikard at p. 56).

- ↑ Ikard at pp. 51-52.

- ↑ King at pp. 8-10.

- ↑ Hudson, David. "Thurgood Marshall in Tennessee: His Defense of Accused Rioters, His Near-Miss With a Lynch Mob." Tennessee Bar Journal. vol. 56. no. 8 (Sept-Oct. 2020), pp. 16-21. Web (tba.org). 8 Feb. 2021.

- ↑ Ikard at p. 53.

- ↑ Ikard at p. 60.

- ↑ Ikard at pp. 50, 59.

- ↑ Ikard at p. 76.

- ↑ Ikard at p. 60.

- ↑ Ikard at pp. 60-62.

- ↑ Ikard at pp. 84-85.

- ↑ Ikard at pp. 84-101 presents a detailed account of the witness testimony and arguments of counsel.

- ↑ Hudson at p. 20.

- ↑ Ikard at pp. 97-101.

- ↑ Beeler, cited supra, at p. 59.

- ↑ Ikard at p. 102.

- ↑ "23 Columbia Negroes Freed, 2 Guilty Ask For New Trial." The Daily Herald. 5 Oct. 1946. p. 1. Web (familysearch.org). 15 March 2021.

- ↑ Beeler at p. 59.

- ↑ Ikard at p. 102.

- ↑ Though the Daily Herald editorial the day after the verdict cited the outcome as proof that blacks could receive a fair trial in the South, the Herald clearly implied that some in the community found the outcome upsetting: "Regardless of what anyone may think of the verdict, and every citizen has a right to his own opinion on that, there is one thing that cannot be disputed.... It may be that some guilty went free; it is certain that none who were innocent were found guilty." "No Prejudice Here." (editorial). The Daily Herald. 5 Oct. 1946. p. 2. Web (familysearch.org). 15 March 2021.

- ↑ Ikard at pp. 103-104.

- ↑ Ikard at p. 104.

- ↑ Ikard at p. 108.

- ↑ King at pp. 7-20.

- ↑ Hudson at p. 20.

- ↑ Ikard at pp. 108-111.

- ↑ Ikard at p. 113.

- ↑ Ikard at p. 111.

- ↑ Ikard at pp. 110-111.

- ↑ King at pp.14-16.

- ↑ Ikard at p. 112.

- ↑ King at pp. 17-19.

- ↑ Hudson at pp. 20-21

- ↑ Ikard at p. 111.

- ↑ King at pp. 18-19.

- ↑ "NAACP Lawyers' Auto Searched, Weaver Protests." The Daily Herald. 19 Nov. 1946. pp. 1. 3. Web (familysearch.org). 15 March 2021.

- ↑ Ikard at pp. 111-112.

- ↑ Ikard at pp. 128-130.

- ↑ Wood, Tim. "Fight to End Racial Prejudice - 1946 race riots." January 2014. Web. 8 Feb. 2021. Wood cites O'Brien, cited supra, at 247-248.

- ↑ Beeler, cited supra at pp. 60-61.

- ↑ Van West, cited supra.

- ↑ Price, Tom and McClellan, JoAnn. "Aftermath of 1946: Dubbed 'riot' was necessary for change in Columbia, America." The Daily Herald. 23 Feb. 2021. Web (columbiadailyherald.com). 27 Feb. 2021.

- ↑ The east side of State Historical Marker 3D-83, on East 8th Street in Columbia, contains a similar claim.

- ↑ Christen, Mike. "How a dispute over a broken radio launched a civil rights movement." The Daily Herald. 24 Feb. 2021. Web (columbiadailyherald.com). 25 Feb. 2021.